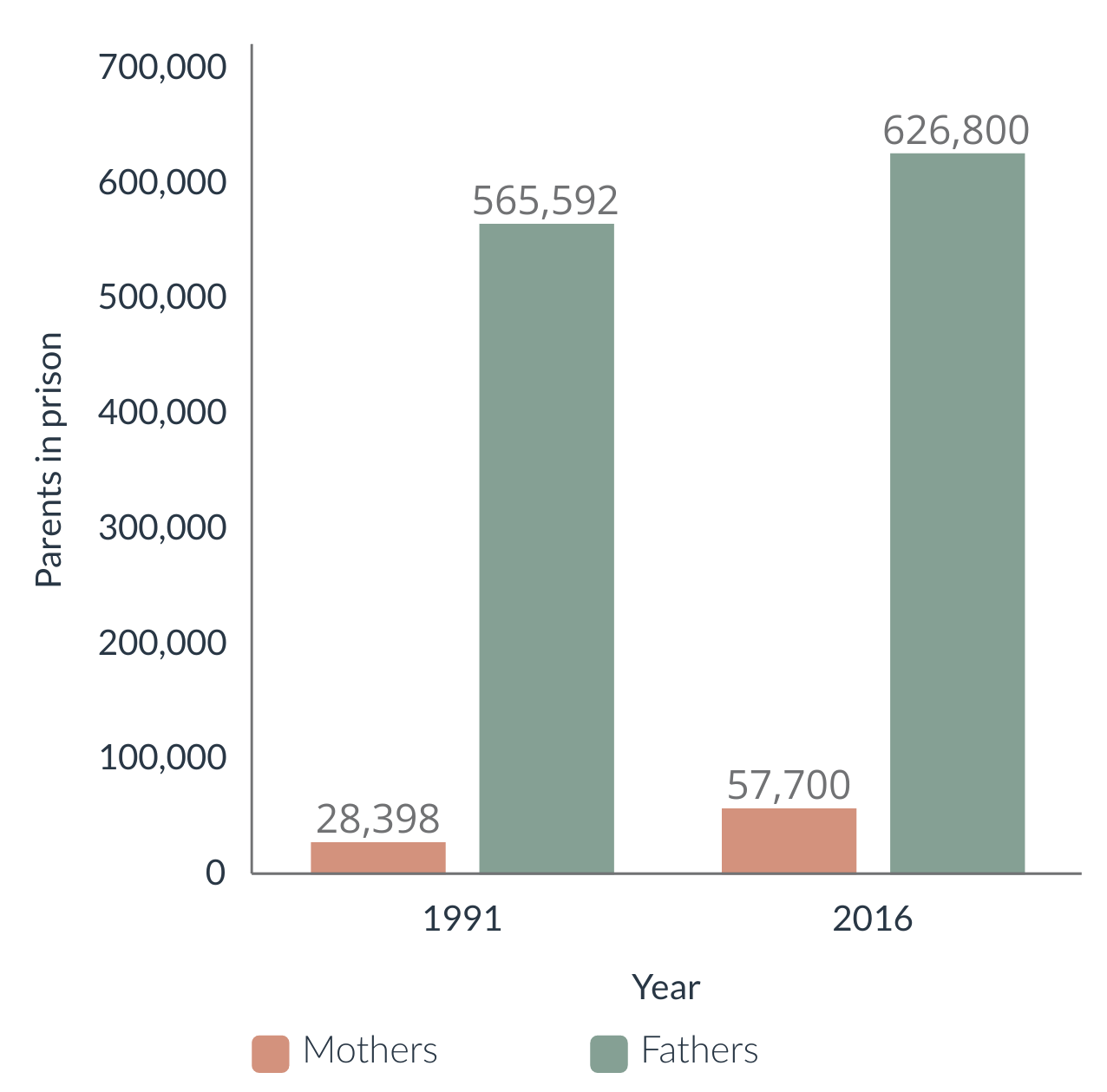

The short- and long-term effects of separation due to incarceration can be devastating to parents and children and have long-lasting detriments to the family and the community. It is well documented that children experience “a shared sentence” when one or both of their parents is incarcerated.1 Seven million, or one in ten, of the nation’s children have a parent under criminal justice supervision—in jail or prison, or on probation or parole.2 The number of mothers in prison increased by 96 percent from 1991 to 2016, and the number of fathers increased by 48 percent during the same period.3 Approximately 80 percent of incarcerated women are mothers.4 In the United States, one of every twelve children—more than 5.7 million—has had a jailed parent at some point in their lives.5 (graph)

Children experience a host of negative outcomes because of a parent’s incarceration, which interferes with the development and maintenance of a strong nurturing bond.6 Being separated from a parent who is incarcerated is an adverse childhood experience (ACE) that may affect the child’s well-being over the course of a lifetime.7 Although rigorous research is lacking on how, specifically, maternal incarceration affects children, several observational studies demonstrate emotional and psychological problems, academic-performance problems, and financial instability.8

Children living in poverty are more than three times as likely to have experienced the incarceration of a parent as children in families with incomes at least twice the poverty level (12.5% versus 3.9%).9 Children of incarcerated parents experience psychological and cognitive problems, which may include depression, conflict with friends and caretakers, and anxiety.10 These children are at higher risk for other mental health concerns, such as abandonment and insecure attachment to their parents, and have a higher likelihood of placement in foster care.11 Children separated from their families due to a parent being incarcerated experience higher rates of physical health problems as well, including migraine headaches, asthma, high cholesterol, and HIV/AIDS.12 These children also suffer from more behavioral problems, such as aggression, delinquency, and poor performance in school (truancy, lower standardized-test scores, dropping out, suspension, and expulsion).13, 14 Research also shows that children of incarcerated mothers have a higher likelihood of other problems such as being sexually trafficked or sexually abused, being uninsured, homelessness, poverty, and feeling powerless.

Family-based alternative-sentencing programs provide an opportunity for families to remain united while caregivers serve their sentences in the community. These programs have the potential to mitigate the negative impacts of separating caregivers from their children, yet only a handful of states and communities currently offer sentencing alternatives.

Family-based alternative-sentencing programs are typically limited to parents with nonviolent offenses, and some serve only mothers or substance-using mothers. Eligibility based on the age of the children varies, with some programs serving only children under six. Core components of these programs include services and supervision. The programs mandate participation in services such as substance use and mental health treatment, parenting-skills classes, vocational and educational programming, and life-skills classes. Community supervision is also a key component of these programs. Washington State, for example, has a specialized team that supervises participants in their family-based alternative-sentencing programs. The community-supervision officers are paired with child-development specialists, emphasizing the importance of parenting as the primary role of the program participant. In Washington, participants can live with approved family members or in program-supported housing, while in California and Oklahoma, women live in community-based facilities, with or without their children, and participate in services onsite.

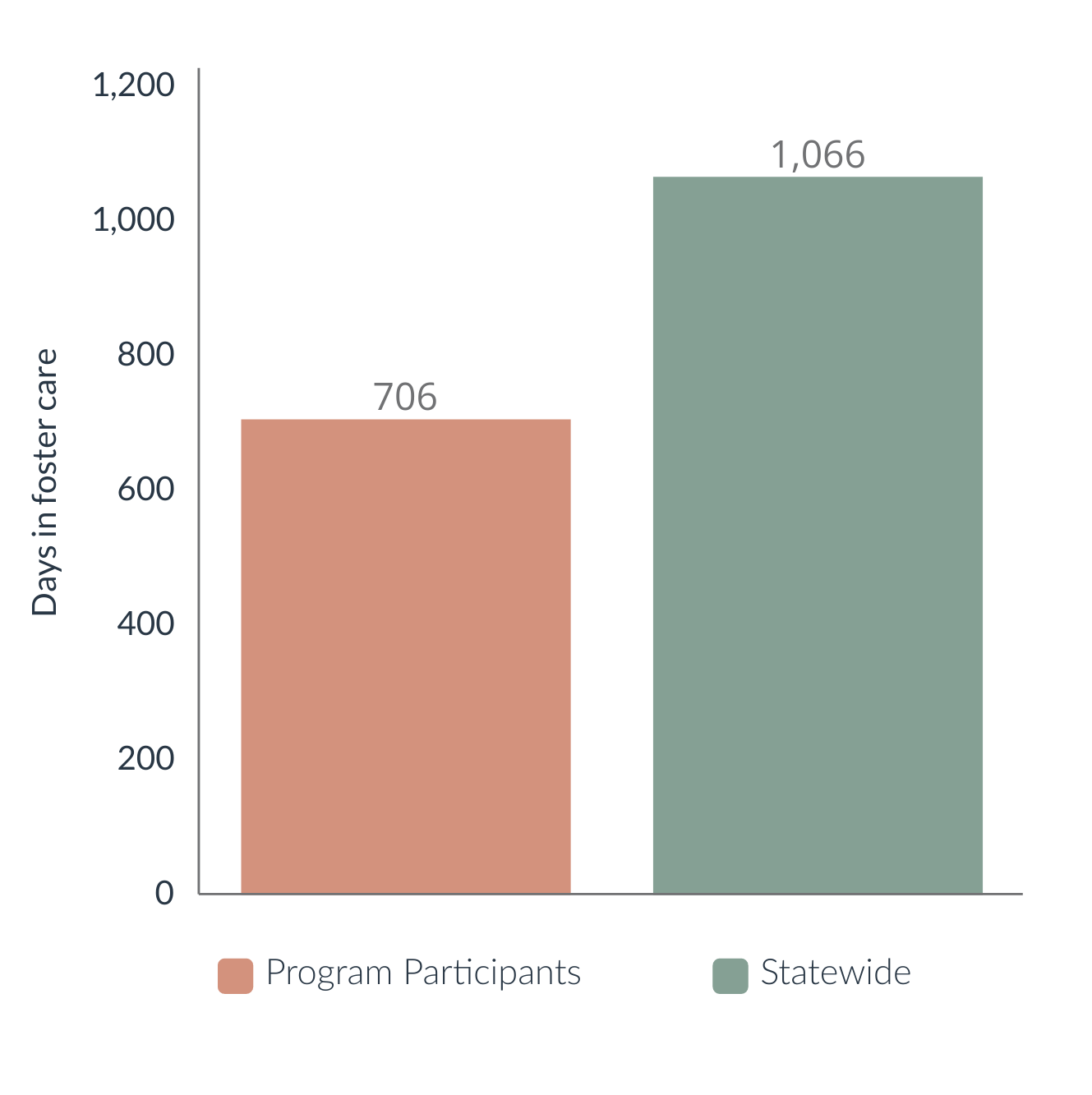

Family-based alternative-sentencing programs have demonstrated promising results. An August 2020 briefing on Washington State’s programs showed that, for the first decade of program operations, through July 2020, 78 percent (N=934) of the participants successfully completed the program and, of the 730 participants who completed either of the state’s two programs, 11 percent returned to prison on a new felony16 (Washington State’s recidivism rate, based on the most recent data, is 32 percent17). The results of a recent study of Oregon’s pilot program suggest that it reduces children’s time in foster care; the average length of stay in foster care for children of program participants in 2020 was 706 days, compared with 1,066 days for children of incarcerated parents statewide.18 (graph)

*Feel free to download the PDF file below and send out to your networks.